In this article, Ross McGill, Executive Chairman and founder of regulatory compliance specialists TConsult, explores the challenges to those financial firms that have signed up to be qualified intermediaries. TConsult works with clients in 27 countries and helps them to understand their exposure to and comply with multiple regulatory frameworks, including QI, FATCA and CRS.

The US investment market has now developed to a point where it represents nearly 56% of the world’s equities value1 It’s the market you can’t easily ignore either as an investor or as a financial institution.

As with any market, there are regulations that address the taxation of income when distributed to a non-resident. For the US these are contained in the US Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Chapters 3 and 4. Chapter 3 deals with the proper taxation of income, such as dividends and interest. Chapter 4, also known as FATCA, deals with anti-tax evasion measures to deter and detect Americans trying to evade US taxes by holding their assets offshore. Both Chapters contain penalties for failure to comply with the rules.

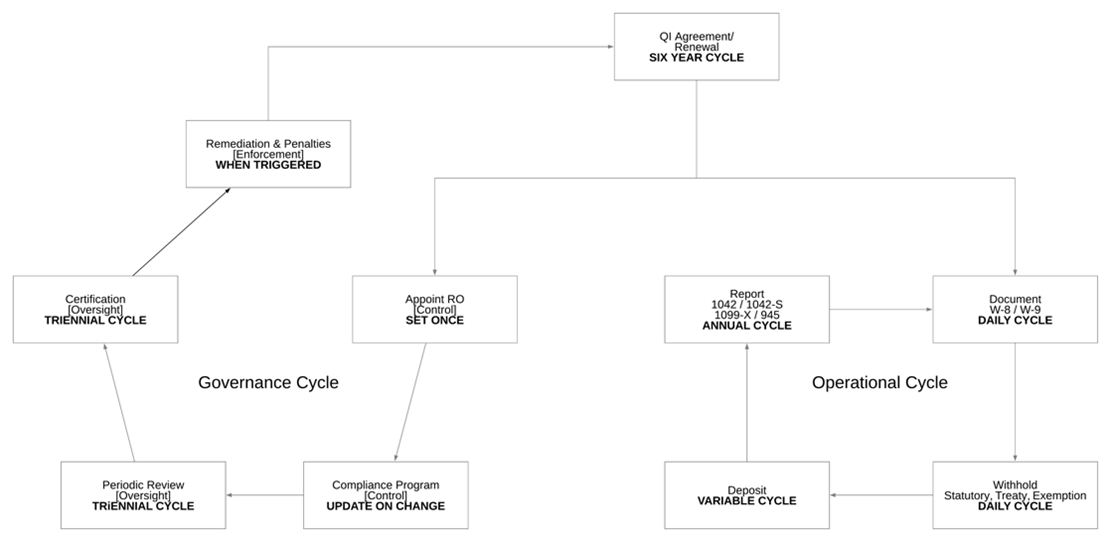

There are two large cycles – operational taxes and compliance. Operational tax has four components (i) documentation of account holders to establish their tax status (ii) withholding of taxes, (iii) deposition of tax to the US Treasury and (iv) information and tax returns. I’ll deal with these in a separate article.

The second cycle operates in parallel with the tax operational cycle. It is the compliance cycle. The compliance cycle has three components (i) control, (ii) oversight and (iii) enforcement. Many firms do not fully understand the context of these contractual obligations and many prioritise tax operations over compliance.

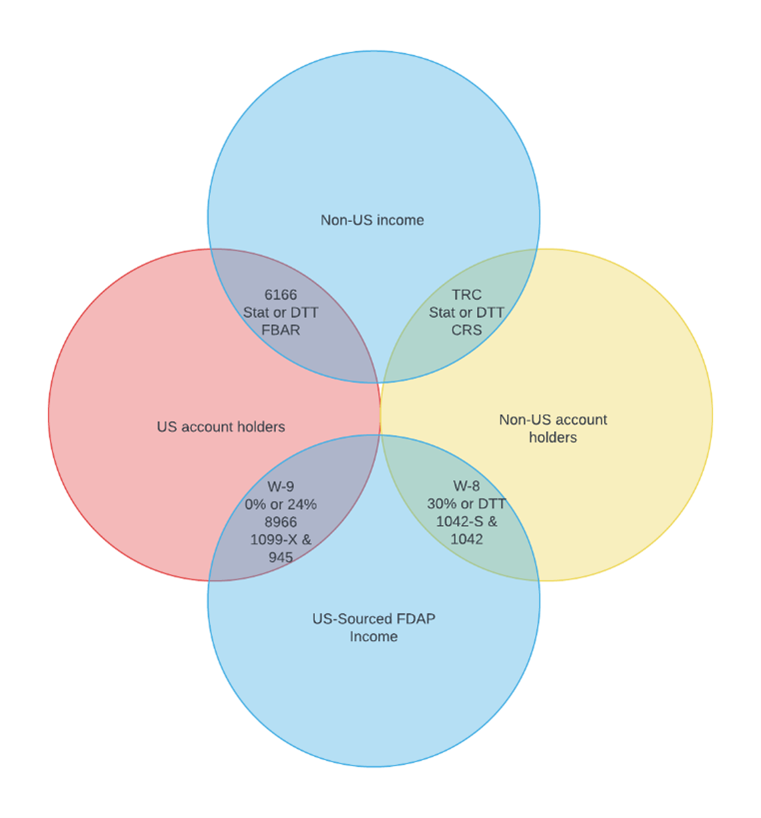

The US, like many countries is also concerned with tax evasion. The US’ anti-tax evasion model is contained in Chapter 4 of the internal revenue code, sections 1471-1474. While Chapter 4 is concerned with identification and reporting of US account holders, even if they do not receive US sourced income to their accounts, Chapter 3 is concerned with accounts that do receive US sourced FDAP2 income. Exhibit 1 shows the possible permutations and impacts where there is overlap.

Exhibit 1. Exposure to US tax regulations

So, the questions to ask are (i) is the account holder US or not (irrespective of whether the account received US income)? and (ii) does the account receive US sourced FDAP income or not (irrespective of whether its owned or controlled by a US person)? This covers three of the four components of the Venn diagram in Exhibit 1. The fourth component represents non-US account holders not receiving US sourced FDAP income. These are out of scope of the US tax regulations and out of scope of the compliance obligations of the financial institutions that hold these accounts.

In this article I will focus on the non-US account holders receiving US FDAP. These are the so-called QI regulations, more accurately referred to as US Internal Revenue Code Chapter 3 Section 1441 NRA3 .

Unlike almost every other jurisdiction, the US system allows non-US financial institutions to become withholding agents responsible for tax withholding and depositing. In almost every other jurisdiction, the only withholding agent is usually a domestic financial institution acting as a sub-custodian for other “foreign” financial institutions.

Withholding agents under Chapter 3 that have signed a QI Agreement with the IRS are known as qualified intermediaries and are subject to contractual controls as well as regulatory controls. Those that do not sign this agreement are known as non-qualified intermediaries or NQIs and are subject only to the regulatory controls. The contractual controls are there to establish a governance framework for the tax operational components of the QI Agreement, namely (i) documentation, (ii) withholding, (iii) depositing tax and (iv) reporting.

Exhibit 2. Governance and tax operational framework

Control

Control for qualified intermediaries has four components. The most basic are the terms of the QI Agreement, the commercial contract between a non-US financial institution and the IRS. The current QI Agreement is found in US Internal Revenue Procedure 2022-434 that became effective on January 1st, 2023. It is 205 pages long, including the preamble, and sets out exactly how and when the QI must meet certain obligations as well as defining the responsibilities of QIs. Most of the obligations fall within the sphere of tax operations, but most of the responsibilities fall into the sphere of compliance.

The IRS also relies heavily on the tax administration of the QI’s host country to enforce controls. It does this by making it a fundamental eligibility criterion for QI status that the KYC rules of a QI’s home jurisdiction must have been approved by the IRS. It's an event of contract default for a QI to fail to notify the IRS within 90-days of a change to its KYC rules. By doing this, the IRS knows that a QI must meet its domestic legal obligations when onboarding new customers.

The IRS also establishes a control point within each QI known as the Responsible Officer (RO). It’s the RO’s job, in contract, to establish written internal policies and procedures that direct the QI’s employees how to comply with the QI contract that the firm has signed. To achieve that, the RO must be someone who has sufficient authority to make changes in the QI’s business to make sure that compliance takes place. In most firms this is usually the head of compliance but is often a director of the firm or someone who has specially delegated authority from the board. The QI Agreement also prescribes that the RO must communicate those policies and procedures to relevant staff – which effectively sets up an obligation for training and change management to monitor the business for any changes that might affect the firm’s ability to meet its obligations.

The RO has other obligations to satisfy compliance. These include control over any systems used in relation to the payment of US sourced income to non-residents.

Oversight

Oversight is the second component of compliance for QIs. The IRS wants to know whether a QI is meeting its obligations under the QI Agreement. It does this by setting up a governance framework comprising regular triennial certifications of compliance each preceded by an independent review of the QIs performance, known as a Periodic Review. This represents oversight. Both the review and certifications are contractual obligations of the RO. Failure to perform either of these tasks correctly or on time, is defined as an Event of Default under Section 11 of the QI Agreement.

The QI Agreement is a six-year contract starting on the Effective Date of the QI’s contract, which is the date the IRS issues a QIEIN5 . However, under certain conditions, the IRS can backdate the Effective Date to January 1st, which can simplify things operationally for the QI in their first certification period because the US tax year is the same as a calendar year.

Most QIs don’t connect these dots. The date that their QIEIN became effective determines their certification period and certification deadlines. The certification period in turn determines when they must conduct a Periodic Review. The Periodic Review is a mechanical test of whether and how a QI has managed its tax operational obligations. The Annex to the QI Agreement provides detailed instructions for Periodic Reviewers. Importantly, when engaging a reviewer, the RO must ensure that the reviewer is both independent and competent. The first means that the Reviewer cannot have been engaged in similar activity for the QI in any of the three years in the certification period. This has led to difficult times for the big accounting firms, many of whom also act as auditors for QIs that includes reviews of their QI risk. They cannot act as reviewers under this rule. Competency is, at present, a subjective judgement by the RO, although we see many Requests for Proposal (RFPs) that require a reviewer to have some experience of the QI Periodic Review process to be eligible to perform the process.

Over a six-year contract period there will be two three-year certification periods and within each certification period an RO will have to decide which of the three years in the certification period the reviewer will use as its benchmark. The rules here can get quite complicated. In essence, if the RO selects year one or two of the certification period as the review year, the RO will have to make their certification by July 1st of the fourth year. If, however, the RO selects year three of the certification period, the RO’s certification to the IRS is not due until December 31st of the fourth year. This makes for some complex advance planning.

So, if a QI has a QIEIN Effective date of January 1st 2023, their two certification periods will be (i) 2023-2025 and (ii) 2026-2028. In the first certification period, if the RO selects either 2023 or 2024 for review, the certification deadline will be July 1st 2026. If the RO selects 2025 as the review year, the certification deadline will be December 31st 2026.

Equally, if a QI has a QIEIN Effective date of, let’s say August 31st 2023, i.e., their QI effective date was not backdated, then the calculation is similar but does not yield the same results. In this scenario, the certification periods will be (i) 2024-2026 and (ii) 2027-2029. This is because the certification periods are calculated based only on whole calendar years as a QI and, in this case, the period from September 1st to December 31st does not count towards the calculation. The certification deadlines are calculated the same way as before so if the RO selects 2024 or 2025 as the review year, the certification will be due to the IRS by July 1st of 2027. If the RO selects 2026 as the review year, the certification will be due by December 31st 2027. All of this works its way back to a critical planning issue – when does the financial institution apply to become a QI or, more accurately, at what point in any given year it decides to make its application? The IRS takes, on average 6-10 weeks to process a QI application and publishes a deadline, usually in November, for QIs to apply and still get a QIEIN by the end of the year. Many firms fail to take this compliance cycle into account when thinking about QI status – because its several years away at that point, but it does make a significant difference.

When it comes to the Periodic Review itself, there is again, a degree of mythos. Many think that a Periodic Review is based on a sample of accounts. This is not true. The QI Agreement requires all accounts that received US-sourced FDAP income in the review year should be analysed. The trigger for the myth is that the reviewer can decide that the number of accounts may not be economically viable or practical to analyse. Under those circumstances, a reviewer can use a sampling methodology to analyse a smaller population of accounts. A reviewer can use their own sampling methodology, if it has been approved by the IRS, or use the safe harbor sampling methodology provided in the QI Agreement. So much emphasis has been placed on this sampling effort that many QIs now think that this is the standard, when it is not.

The certifications themselves are made by the RO at the IRS web site for QIs (QAAMS6). Many of the statements made on these certifications are drawn from data collected during the Periodic Review. The IRS calls this “Factual Information” and it’ll be repeated every three years.

There are some small concessions made to QIs that have limited exposure to US securities in that if they have less than $5m in reportable amounts, they can ask for a waiver of the Periodic Review process. If granted, the workload is lower but the QI must do all that work themselves i.e., a waiver of the Periodic Review does not mean a waiver of the certification requirement.

The net message is that the IRS takes compliance very seriously. The mechanisms of control and oversight mean that many QIs incur substantial compliance costs, none of which benefit their clients financially. These are costs of doing business with the United States of America.

Enforcement

Of course, in any system of control and oversight, the final component is enforcement. This applies to both the regulatory aspect of a QI’s compliance as well as the compliance aspect.

The most common area of enforcement based on regulation occurs in the tax deposition and reporting. The regulations provide a formula for when US taxes need to be deposited with the US Treasury. Typically, the more tax that is due, the more frequently it should be paid. For tax amounts less than $200 in a year, payment can be made annually. For tax payments that are more than $2,000 in any quarter month period, the tax must be deposited every three days. There are penalties associated with late deposition of taxes.

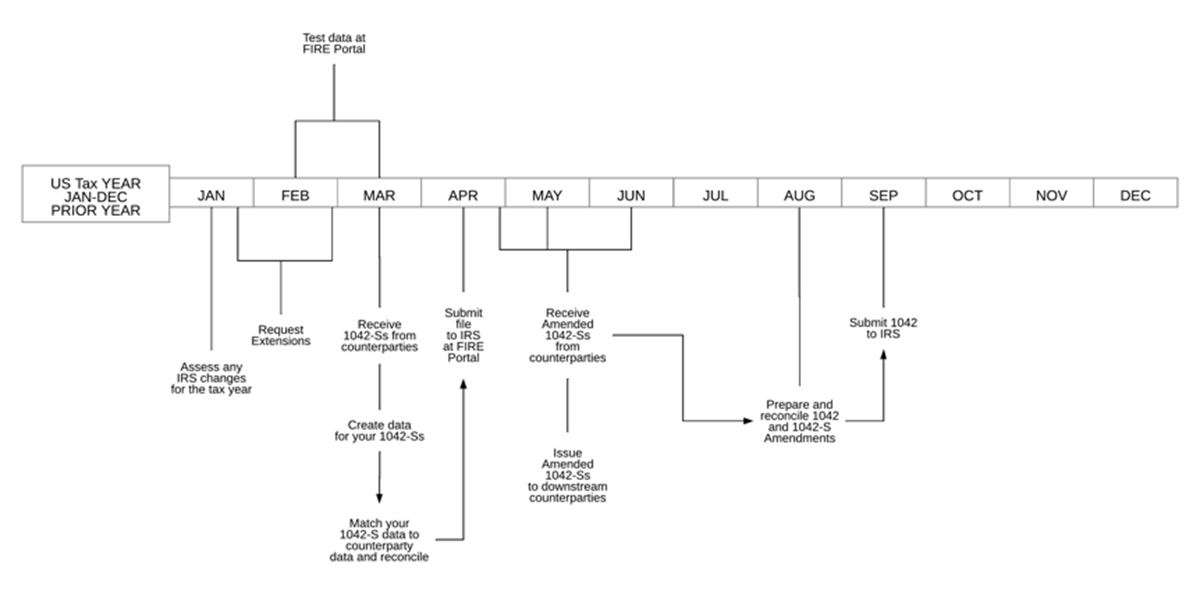

Reporting for a QI is usually on information returns Form 1042-S and annual tax returns on Form 1042. The deadline for both these returns is March 15th of the year following the reporting year. So, income received in 2023 will be reported by March 15th, 2024. However, payment of US sourced income is usually in a chain that can consist of several layers with each layer having its own reporting requirements depending on their US tax status as a QI or NQI. The IRS allows firms to apply for extensions of time to file and almost everyone applies for these extensions in February each year using Forms 70047 and 88098 . In addition, certain types of US Issuer, notably US mutual funds and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), can re-classify income after the end of the US tax year. When this happens, the normal reporting cycle is disrupted by the issuance of amended 1042-S forms. These amendments must then be reflected all the way down the payment chain with each layer changing their returns in proportion to the effect of the change on their payees. As a result, the 1042-S and 1042 reporting cycle is a nine-month process, whereas most QIs think of it as something that happens only in March and April each year.

Exhibit 3. 1042-S reporting cycle explained

The result is that there are penalties for inaccurate or misleading reporting and late reporting. In a worst-case scenario, the IRS can determine that returns are so late that they represent an intentional disregard of the regulations and are thus subject to the highest penalties.

The penalties themselves are changed each year and can be found at the IRS web site9.

In addition, QIs have enforcement rules established contractually in the QI Agreement. These are categorised as either Material failures (lesser failures) or Events of Default (major failures). It is important to understand the connection between these compliance failures and the certification process.

The IRS assumes that the RO has procedures in place to detect any failures of compliance it may have during any particular year. This flows from the RO obligation to have a written compliance program document. While the certification process occurs every three years and the Periodic Review is of one specific year, when a certification is made, it is with respect to all three years of a certification period, plus any portion of a prior year where the firm acted as a QI.

If material failures are detected and cured before a Periodic Review takes place, this is evidence of effective internal controls. The RO can make a normal certification to the IRS. However, if the RO only detects a Material Failure or Event of Default because of the Periodic Review and has not corrected it by the deadline for the certification then, by definition, the QI does not have effective controls i.e., the RO did not spot the problem(s), someone else did. In this case, the RO will need to make a different kind of certification, called a qualified certification. A qualified certification requires the RO to disclose uncured Material Failures and Events of Default, and present an attestation that the failures will be corrected and a remediation plan to show how they intend to correct the failures.

To conclude, the IRS has thought carefully about the implications of allowing non-US financial institutions to act as withholding agents and has constructed a comprehensive and detailed framework of compliance that sits alongside the tax operational components of their day-to-day operations. Concessions to this framework for small firms are few and far between. Indeed, some smaller firms have opted for NQI status rather than meet the effort required for QI status.

End

[1] [Note paywall] https://www.statista.com/statistics/710680/global-stock-markets-by-country/

[2] Income from sources inside the USA categorised as Fixed, Determinable, Annual or Periodic. Most commonly dividends from US corporations, portfolio interest from corporate and government bonds and distributions from US Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

[3] Non-Resident Alien

[4] https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-22-43.pdf

[5] Qualified Intermediary Employer Identification Number

[6] https://www.irs.gov/businesses/corporations/qualified-intermediary-system

[7] https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-form-7004

[8] https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-form-8809

[9] https://www.irs.gov/irm/part20/irm_20-001-007r#idm139667299197488